Some scientific experiments, such as in quantum physics, are complex because of the ‘observer effect.’ The presence of an observer changes the behaviour of what is observed. It would be like the BBC coming into your home with their cameras to do some filming. I’m sure everyone in the family would be watching their ps and qs!

Ash Wednesday marks the start of Lent, a season of personal and communal renewal. The Church undertakes Lent in order to accompany Jesus on his journey to Jerusalem to his Death and Resurrection. In Him, we die to sin; in Him we rise to life. Lent invites us to die to sin and all that is not right, in order to rise in Him to a renewed way of living. That’s why the Church uses ashes. Ashes remind us of our mortality, that ‘you are dust and to dust you shall return’ (Gen 3: 19) and that we need to ‘repent and believe in the Gospel’ (Mark 1: 15). The Christian life is an unending combat. Fighting against evil in ourselves, dying to self to live for God, struggling against selfishness and injustice in self and others, is the ascetic journey every disciple is called to make generously.

As a child, I used to think Lent was a time to give things up, such as not eating chocolate or sweets. Easter Sunday was great, when gorging on Easter eggs, life could get back to normal! Yet the word Lent comes from the Anglo-Saxon ‘Lencten’ (‘when the days lengthen’). It means Springtime. Lent is a spiritual springtime. It’s a joyful season, as the Roman Liturgy puts it, a time when God wants to give us new grace and new life. St. Leo and the Fathers of the Church remind us that there are three works to undertake in Lent, not just self-denial, but works of prayer – particularly going to Confession and attending Mass – and almsgiving, works of justice and charity, helping the poor and needy. Jesus refers to these works in today’s Gospel (Mt 6: 1-6, 16-18). These works are our response to God’s gift, to bring about a fresh start.

Thinking again of the ‘observer effect,’ this Lent, I’d like to suggest we try something. Let us examine how we ‘come over’ to others, how we relate to them, the attitudes we show to certain people, the impact our personality makes on others, the good or the bad effect we have on those around us. Like those experiments in physics, it’s not always easy to work it out. Do I bring joy to others – or pain? Do I put others at ease – or make them feel uneasy? Do I show kindness to others – or indifference? Yet ‘we are ambassadors for Christ,’ St. Paul tells us, and ‘now is the favourable time; now is the day of salvation’ (2 Cor 6: 2). Self-awareness is not easily achieved: if only it were as simple as inviting the TV cameras into your home! But unless in prayer we try, we’ll never grow in holiness; we’ll never become the sort of person God wants us to be; we’ll never grasp the Lenten promise of new life and resurrection.

Rt Rev. Philip Egan is the Catholic Bishop of Portsmouth. In 2010 he was appointed Vicar General of the Diocese of Shrewsbury, in 2011 a Prelate of Honour to His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI and in 2012 a Canon of Shrewsbury Cathedral. Bishop Egan is a member of the Bishops’ Conference Department for Evangelisation and Catechesis

‘Man does not live on bread alone but on every word that comes from the mouth of God.’ (Matt 4:4)

‘Man does not live on bread alone but on every word that comes from the mouth of God.’ (Matt 4:4)God is good, in faith we know he gives us everything we need. With this sure hope we begin this Lent pondering what we might learn from this Sunday’s Gospel (Matt 4:1-11). There are two themes (among many) I would like to explore: the importance of Scripture, and what it means to enter a wilderness.

In the wilderness Jesus stands firm against the temptations of Satan, using scripture as a weapon. We too can arm ourselves with this living gift of scripture to guide us every day to an encounter with Jesus himself.

In this Sunday’s reading we encounter the power of Jesus’ word – ‘man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes forth from the mouth of God’(Matt 4:4). How, this Lent, will the words which come from God’s mouth be the most essential part of your day, the thing from which you draw life, the place where you encounter Jesus himself?

As Southwark’s Agency for Evangelisation and Catechesis, we meet in person at the beginning of each week, always beginning with a period of prayer, most often Lectio Divina. This prayer is without fail a source of joy, hope, inspiration and a place of encounter with Jesus. It prepares us for the work that we are called to do. As a team we have come to see that it is the word that sustains us, inspires us, humbles us and helps us see more clearly what we need to do as we work supporting evangelisation, catechesis and formation in Southwark. Our encounter with scripture helps us to pray for wisdom, and the ability to do our job right, to strip back our own personal preferences and learn to trust each other as we seek after the Lord together.

When Jesus enters the wilderness, he does so to spend time in prayer with his Father – something he did repeatedly during his ministry. As we enter our Lenten ‘wilderness’, I encourage you to do so in order to seek an encounter with Jesus, the Word. What can we do to still some of the busyness of our lives in order to encounter the Lord every day? Perhaps consider using this Lent as a time of retreat into scripture – a time to build and nourish your inner spiritual life.

Although it is good and necessary to find time for quiet and solitude, it is important to remember that our faith is not a private journey. It is meant for sharing with others. In doing so, those you encounter will help you become more aware of God’s endless and generous outpouring of grace into your life to enable you to continue to answer His call.

We can all identify with moments in our lives where we enter a ‘wilderness’, a place where we lack spiritual consolation. For because ‘we walk by faith, not by sight’, we perceive God as ‘in a mirror, dimly’ and only ‘in part… our experiences of evil and suffering, injustice, and death, seem to contradict the Good News; they can shake our faith and become a temptation against it.’ (CCC 164)

When our faith is shaken, and we are vulnerable we can be tempted to begin to believe that we are alone and that we are not loved. As Christians we know this can never be true for we are never alone and we are always loved. When we are tempted in our ‘wilderness’ if we have developed a love for Scripture we can be sure that we can turn to the word of God to be comforted, for ‘your word is a lamp for my feet, and a light for my path’ (Psalm 119:105).

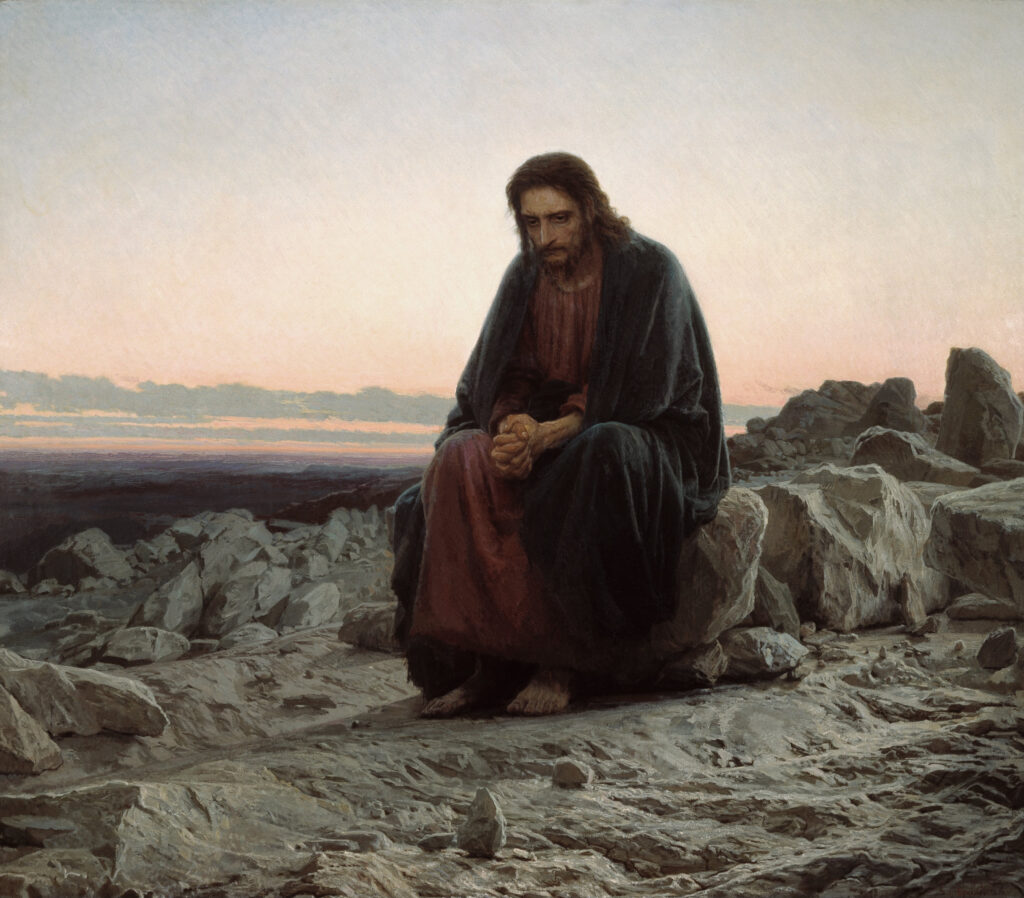

For we are an Easter people. As you ponder the image of Christ in the Wilderness that accompanies this post, remind yourself of what comes next – baptism in the Jordan, with the appearance of the Holy Spirit, the calling of the disciples, many miracles and vast crowds, the triumphant entry into Jerusalem and then the ‘wilderness’ of the cross, followed by the glory of the Resurrection and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Jesus, who is love, was never alone in the wilderness. In your Lenten ‘wilderness’ you are never alone, and you are always loved. God is good, in faith we know he gives us everything we need. This Lent I encourage you to spend time increasing your familiarity with Scripture, through prayer. Your time with scripture is an essential part of your Christian journey, for we do ‘not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes forth from the mouth of God’ (Matt 4:4).

Mrs Ingrid La Trobe works for the Agency for Evangelisation and Catechesis in the Archdiocese of Southwark as the Advisor for Family, Child & Youth Catechesis. She has over 20 years of extensive parish catechetical experience supporting families passing on their faith to their children. Married for over 30 years and a mother of five, Ingrid is an avid walker, completing the Camino Frances in 2016, and the Camino Portugues with her 3 sons in 2019. She frequently walks parts of the Pilgrims’ Way to Canterbury which runs through her parish of St Thomas of Canterbury, Sevenoaks.

‘His face shone like the sun.’ (Matt 17:1-9)

In the Gospel today, we are invited into a personal moment that Peter, James and John are experiencing. Just ahead of preparing this reflection I had been reading the book of Daniel and his vision of the Son of Man (Dan 10). It struck me that there are distinct similarities between the events. It reminded me that as Jews, the disciples would have been familiar with the vision of Daniel, and this would have helped them to understand the significance of what they were experiencing on that mountain. The Father was revealing Jesus to them as someone greater than Moses or Elijah, that he is in fact the Son of Man as revealed in the book of Daniel, the Messiah who they had been waiting for their entire lives.

The disciples have this encounter up a mountain – mountains are the place of meeting between God and his people in the Old Testament, there are so many examples of this and of course, both Elijah and Moses meet with God up a mountain. Jesus tells them not to tell anyone until after ‘the Son of Man has been raised from the dead’. So they are now under no illusion that Jesus is talking about himself because they understand now that Jesus is in fact this mysterious figure described in the Book of Daniel.

The Transfiguration then points towards the coming salvation through the death and resurrection of Jesus. As we noted earlier, mountains are the meeting place between God and his people. Jesus dies on Golgotha, a hill outside of Jerusalem. In fact, some scholars think that Golgotha is also Mount Moriah where Abraham takes Isaac to be sacrificed. This mountain, where Jesus dies is the ultimate meeting between God and humanity; the place where heaven touches earth, the place of encounter where Jesus dies so that we can live. Or as St. Paul puts it in our second reading where ‘…the appearing of our Savior Christ Jesus, who abolished death and brought life and immortality to light…’ occurs.

This moment, as Jesus dies on the cross, is the moment that the transfiguration is pointing us towards. As Jesus dies on the cross, there is darkness, yet at the moment when Jesus dies, light breaks through: ‘…and there was darkness over the whole land until the ninth hour…’ (Luke 23:44).

So, light has in fact overcome darkness, life has overcome death, for three days later Jesus rises to new life. That glimpse of the Jesus transfigured on the mountain is now a reality – he is the true light that has overcome the darkness, the Lord of light. He calls us to come to him, to give him our sin and brokenness and to receive his new life. We too are also called, like Abraham in the first reading, to be a blessing to others, to draw all people to His life, because He loves each one of us and wants every person to know His love, glory and plan for their life.

Dr Maria Heath, Director of Mission Northampton.

‘A spring of water welling up to eternal life.’ (John 4:5-42)

One day a candidate preparing for the sacrament of reconciliation asked a priest, ‘Will Jesus really forgive me?’ The priest asked the candidate in return, ‘Do you throw away your dirty clothes?’ ‘No,’ came the reply. Then, neither Jesus our Lord will throw you away.

In the encounter between Jesus and a Samaritan woman, we learn that despite how the world must have treated the Samaritan being sinful, Jesus saw in her the possible missionary that she could be with His encouragement. No matter what our past must was, our future is pure and spotless.

The word water is repeated several times in this passage. In certain parts of the world, we have water in abundance and must not have experienced what the scarcity of water is, like in parts of the world where they need to walk miles to fetch a jar of water. If there is no water, there won’t be any life. Therefore, when Jesus speaks about living water in today’s Gospel, He is referring to life which is His own self.

It is always the Lord who takes the first initiative to reveal Himself as we see in today’s gospel reading. The whole scene starts as an encounter between two strangers which gets evolved into a mystical transformation and missionary action from the side of the Samaritan woman. The Lord continues to reveal himself through simple day-to-day conversations if we listen to his voice which comes through the people.

St Augustine said our hearts are restless until they rest in the Lord. Here in today’s gospel reading we find the same thirst in God too. It is a paradoxical scene; the giver of the living water is thirsty Himself. The thirsty Messiah and the woman who was in thirst of the living water meet. The voice that echoes in this passage is that ‘my child, my heart is restless until I encounter you, talk to you, listen to you, sit with you and dine with you’. It is a wonderful way to understand how God and humanity are thirsting for one another.

This passage gives us a glimpse about the power of God’s mercy and love. When Jesus meets this woman, He brings up her past into the conversation not to condemn her or to punish her but rather to reveal Himself to her. Let us pay attention that the name of the woman is unknown, it is left blank by the author so that we can fill with our own names. No matter who you are and what you have done, you are special, precious and loved by God Himself. This is the good news that the Lord gives us today. Our day-to-day experiences and encounters can be transformative and life changing. Let us be attentive to what happens around us and let us thirst for God in all that happens and in all that we do.

Fr Joseph Raju Katthula CMF, is a Claretian Missionary, based in the Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish in Hayes. He now works as the Religious Life Promoter at the National Office for Vocation.

‘He went off and washed himself, and came away with his sight restored.’ (John 9:1-41)

‘We must work the works of him who sent me while it is day; night is coming, when no one can work. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world.’ (John 9: 4-5)

The healing of the man born blind through the miraculous power of Christ offers much for reflection in our modern day. The lengthy account captures both the great potential for restoration through the merciful love of God as well as the many human obstacles to the healing ministry of Christ, both then and now.

We are immediately challenged by the perennial problem of pain and the difficult, yet unavoidable, question of how and why a good God can allow suffering to persist when He surely has the power to prevent it. The passage begins with an encounter of ‘a man blind from birth’ whose lifelong illness prompts the disciples to ask Christ, ‘Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?’ Their very human instinct to attribute suffering to some sort of private failing is rebuked by Christ who invites his followers to view the man and his situation through the eyes of faith: ‘It was not that this man sinned, or his parents, but that the works of God might be displayed in him.’ Christ then anoints the man and invites him to wash himself in a pool, the combination of which restores his vision.

At this stage, we might look at this passage suspiciously and query if the blind man has been unfairly made to suffer to serve as a teaching prop for Christ in his ministry. However, that would miss the underlying message of the account which has much less to do with suffering per se, and much more to do with our free response to the grace of God. Christ comes to save us but not to suppress our freedom, even if we use that freedom to reject the medicine of his grace.

The dismissive responses of the Pharisees and Jews to the report of the healing of a blind man reveal the human potential to deny Christ even in the face of his wondrous works. The Pharisees deem Christ to be a sinner for carrying out work on the Sabbath, even the work of healing, while the Jews reject the possibility of Christ doing the will of God because of his claim to be the Messiah. Although both communities are confronted by the sight of the healed man they instead turn away and narrowly focus on their own limited understanding of law and history.

In stark contrast, the healed man submits to Christ having witnessed his healing power, despite his limited grasp of events. Even though he sees ‘in a mirror dimly’ (1 Corinthians 13:12), he submits in obedience to the power of God and co-operates with His grace, in the same manner of co-operation with divine blessing as healed him in the first place. As we read and reflect on this passage, we might ask ourselves whether we are open and willing to take that leap of faith in response to God’s grace in our lives or whether we, like the Pharisees and Jews in this passage, constrain God and His works to a mechanism of our own making.

Naoise Grenham works as a Policy and Research Analyst at the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales.

‘I am the resurrection and the life.’ (John 11:1-45)

This reading gives us glimpses of hope. But it is easy to focus on Jesus’ own resurrection and miss other important elements in this reading. Let’s take Mary, for example. She is mentioned first, so it is possible she was the eldest in the family of the three siblings (Mary, Martha and Lazarus).

Inexplicably at first, Jesus does not respond to the heartfelt plea of the sisters, and Lazarus dies. Four days on, there is still mourning, and Mary seems paralysed. She remains seated in the house even with the news of Jesus’ proximity. This will echo with many of us who have lost a loved one. Grief triggers inner exhaustion, a near paralysis that turns us into the shadows of ourselves. Even rumours of eternal life seem to be too distant to spur us into action.

Mary needs her sister, the ever-fretting Martha, to come to her after encountering Christ and making the most eloquent profession of faith. Martha whisper into Mary’s ears: ‘The Teacher is here and is calling for you’. Jesus is called a teacher. Not a prophet, not a messiah, a teacher. So, what is it that Mary needs to learn? And what is it that I need to learn about grief and the place of Jesus vis-a-vis my pain?

Mary rises quickly and the consoling crowd notices it. Remarkably, the first word that describes Mary’s rising (egeiro) has connotations of waking from sleep, the mini-death of the ancient world. It is the same rising of Joseph to fly to Egypt, the rising of the paralysed man who fetches his mat, the rising of blind Bartimaeus. However, what the crowd notices is Mary’s rising (anistemi), a word connected later with Jesus’ own resurrection. Something has changed in Mary, and it is obvious to the bystanders. Perhaps we could try to recognise what has brought us an inner awakening in similar situations. Perhaps we can listen out for the words that might bring us round if we are still stuck in overwhelming grief.

Unlike her sister, Mary draws a crowd before she falls at Jesus’ feet. She repeats the first bit of what her sister has already said: ‘if you had been here…’ But she makes no profession of faith. Her raw tears and tears of her consolers move Jesus profoundly. After his own words from John 1:39 are echoed back to him, Jesus weeps.

Despite her private profession of faith just moments ago, Martha objects to Jesus’ instructions to take the stone away because of the stench of death. Mary is not mentioned anymore here, but we know that something profound is quietly forming in her heart. In the next chapter she anoints Jesus’ feet with an extremely expensive ointment and the sweet fragrance fills the house. It is the fragrance of her gratitude, faith and understanding of what is ahead of Jesus. Perhaps we could sit with Mary today for a while and allow her to show us how grief could change into tender anointing.

M.C. Benitan is the Director of Pastoral Development at the Archdiocese of Liverpool, spiritual director, retreat giver, teacher, artist, and theologian. Her passion is for God and the flourishing of all God’s creatures. Her medium is the Word, silence and creation – artistic or natural.

‘The passion of our Lord Jesus Christ.’ (Matt 26:14–27:66)

Light and dark in Matthew 26:14 – 27:66

Matthew’s Gospel shifts between light and dark with a similar deftness to Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro in ‘The Taking of Christ’ heightening the range and intensity of betrayal. We’ve leapt from Palm Sunday joy to Judas betraying Jesus with a single kiss. It’s easy to blame everything on Judas since his treachery is the turning point of the Passion. Yet, he is not the only one to fail Jesus as he walks towards his death.

The Passover meal is filled with clues, but the disciples have still not understood. Who would betray their Lord and friend? The Garden of Gethsemane is no longer a place of peace but of extreme stress and exhaustion. Jesus begs God to forgo his imminent suffering while James, John and Peter are fast asleep. They provide no back up when his life is hanging by a thread.

Suddenly Jesus is surrounded by violent crowds wielding swords and clubs, so unlike the gentle palms that greeted him days ago. While he has nowhere to run the disciples disappear before the scriptures can be fulfilled. Desperate to bring him down, the Chief Priests and Council accuse him of blasphemy. Meanwhile, Peter hides in the courtyard unaware that his own judgement by cockcrow is imminent.

In the civil court Pilate is confused and conflicted which is dangerous for the agent of imperial justice. His decision changes history as light and dark continue to battle it out amid images of 30 pieces of silver, a crown of thorns and a total eclipse. The people under instruction from their leaders reject the Messiah for a common thief and Jesus humbly surrenders to their will. Women are wailing, stricken with grief but unlike the disciples they stay the course.

There is blood everywhere: the blood of the covenant drunk from the Passover cup; the blood from the servant’s ear sliced off in the garden; the blood money returned by Judas before hanging himself; the blood of innocence and blessing from the tortured body of Christ crucified.

Amid all this drama as the Temple Curtain tears apart there’s a challenge: do we stay with Christ to the bitter end? Can we see the presence of God in a new light? In Caravaggio’s painting, look at how Jesus locks his hands ready to be bound as Judas kisses him to his death. There is moonlight but the darkness of deceit dominates the scene. The guards press in to secure his arrest, they cannot afford to get this wrong. There are seven figures: left to right they are John in despair as he rushes away – his scarlet cloak flying high as a soldier snatches it back; then Jesus as he looks down upon his destiny while clutched by Judas unable to look him in the eyes; two other soldiers; and a lantern held by a man who is possibly Peter.

In the sheen on the soldiers’ armour Caravaggio invites us to reflect on this event and see ourselves within the picture. When Jesus dies on the cross, he forgives the world its sin and offers forgiveness to all who will come after him. Outstretched and outcast he is not outdone.

Fleur Dorrell is Catholic Scripture Engagement Manager for the Catholic Bishops’ Conference and for Bible Society and the national co-ordinator of the God who Speaks initiative.

‘He must rise from the dead.’ (John 20: 1-9)

Every Easter Sunday morning an old man climbs up to a balcony and proclaims, for all the world to hear, that the Lord is risen, He is risen indeed, alleluia! That man is the Pope. Giving his blessing to the City and to the World, Urbi et Orbi, he proclaims once more the Church’s life-saving, world-changing message – that death does not have the last word, that life is victorious, that love lives again.

Our Pope, Pope Francis, can proclaim this message, ever old and ever new, because on that first Easter Day our first Pope, Peter, with his brother-apostle John, saw an empty tomb – and in seeing it knew it was all true. They saw and they believed. Everything that the Lord had promised them they were seeing with their own eyes. Mary Magdalene’s message that the stone had been rolled away had set them running. She, the first witness of the resurrection, was the first to proclaim the news. Mary and Peter and John, their whole lives long, had this news to share, seeing and believing. Many faces with many voices have proclaimed it ever since.

This Easter Sunday in this year of our lives, we have that same news to share, and it is good news for all who struggle, who mourn, who weep, who wait, who never stop hoping. It is news which ‘dispels wickedness, washes faults away, restores innocence to the fallen, and joy to mourners, drives out hatred, fosters concord, and brings down the mighty.’ (From the Exsultet, the Easter Proclamation). Pope Benedict XVI puts it powerfully: ‘Faith in the resurrection of Jesus says that there is a future for every human being; the cry for unending life which is a part of the person is indeed answered…God exists, that is the real message of Easter. Anyone who even begins to grasp what this means also knows what it means to be redeemed.’

Nearly 25 years ago, shortly after my ordination as a priest, I was sent as Chaplain to our Diocesan Youth Centre. In our Prayer Room at the top of the house, our very own Upper Room, we had a bold and powerful sculpture by the artist Lyn Constable Maxwell, ‘The Risen Christ at SPEC’. At the centre of it was the figure of Christ, crucified and broken, and around him, a golden figure, big and with arms stretched wide. Something small and ugly becoming something big and beautiful. Praying with that sculpture every morning before our working day began, our youth team – and me – drew inspiration, encouragement and strength. The Risen Christ changed – changes – everything.

So, with Easter faith, hope and love we keep on running, seeing and believing, with lives transformed, and proclaiming as we go…… the Lord is risen, He is risen indeed, alleluia!

After some years in Anglican Ministry Fr Chris was ordained as a priest for the Diocese of Westminster in 1997. He has served in hospital, prison, youth and vocations ministry, and in parishes in East, West and Central London. He is currently Director of the Westminster Agency for Evangelisation and parish priest of St Mary Moorfields in the City of London and St Joseph’s, Bunhill Row.